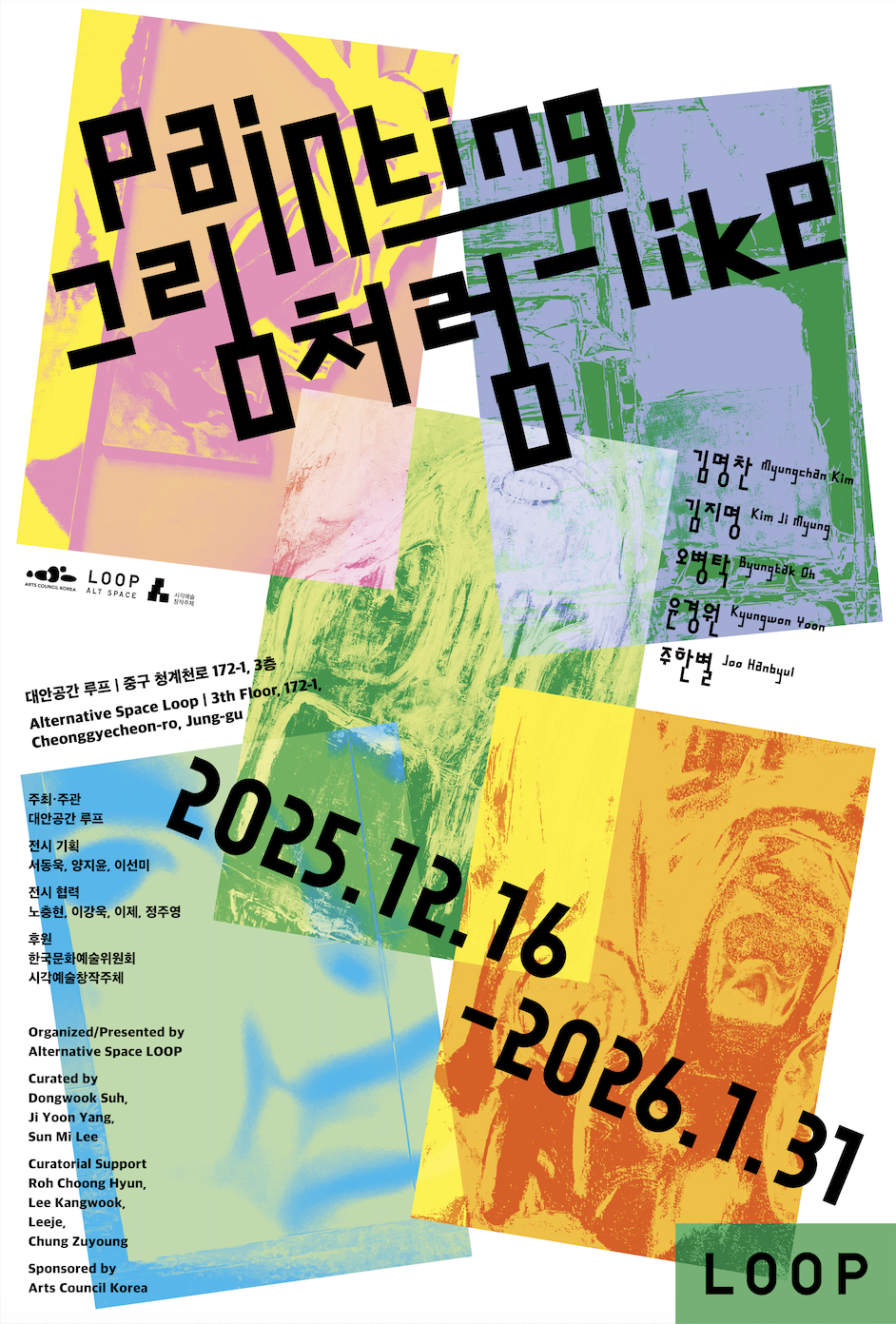

The inaugural exhibition Painting-like is a presentation of five emerging painters, developed in curatorial collaboration with five established mid-career artists. Initiated to address the uneasy distance between contemporary art discourse and painting practices, the exhibition affirms our continued belief in the vitality of painterly practice and the depth of experience it offers viewers. We look forward to welcoming you at the opening of our new space.

-

Questions

For the second year in a row, I have been invited to curate a painting exhibition at Alternative Space LOOP. Within the mainstream art world of museums and biennials, painting has become increasingly marginalized. If we look at the roster of nominees and recipients for the Korea’s most prestigious art award, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Korea Artist Prize, painters are extremely rare. I do not have precise statistics, but given that painting still makes up an overwhelming portion of artistic production, the imbalance between mediums is striking. I am critical of museums that privilege art dependent on language, a narrow notion of political correctness, and sheer spectacle. Meanwhile, at art fairs such as Frieze or Kiaf, it seems that roughly 90 percent of what is shown are paintings. I am equally critical of this extreme commercialism in art. One of the key questions in curating this exhibition was: if so many people enjoy looking at paintings, why are museums unable to recognize painting as a serious art form? If the public sphere of art continues to refuse to engage seriously with painting, then painting will be forced to compromise with commercialism, guided only by the metrics of “likes” and capital’s choices.

Just as painting once faced the challenge of photography in the nineteenth century, contemporary painters now confront the challenge of artificial intelligence. In the near future, advances in technology will render image generation easy and ubiquitous. In fact, in fields that require the rapid mass production of images—commercial illustration, concept art, background images—AI is already encroaching. This leads to a second question that underpins this exhibition: will AI eventually replace painting as well? Here I focus on “drawing” as a physical activity of the human body and on the materiality of painting itself. The process by which a painter paints is marked by a distinctive uncertainty: the brush slips, pigment bleeds, things are ruined, erased, painted over, and at times begun again on top of what was already there. This unpredictable, stubbornly material experience does not remain in digital media. I believe that the specificity of painting emerges precisely in the interplay of the painter’s deliberate choices and inevitable failures, in the frictions, accidents, mishaps, and revisions that arise when matter refuses to submit entirely to the painter’s will. Painting is one of the most primal activities humans have practiced since the time of caves, and it remains one of the most valid—and most human—ways of making.

The relativity of beauty — In the past, there were ideal standards of beauty; today we acknowledge a wide range of contexts—race, gender, bodies, identities, cultural backgrounds—and the criteria of beauty have grown correspondingly complex. A relativist perspective in art is democratic in the sense that it frees us from uniform standards and respects diversity. Yet the notion that anyone can be an artist and anything can be art results in a different kind of homogenized relativism. It disarms the question, “Is this a good painting?” I am convinced that there are indeed clear differences. Paintings that are skillfully made, that have been worked on with care and persistence, reveal their quality to those who are willing to look closely.

Reactionism in paintings — Recent paintings tend to revisit and reinterpreting traditional genres such as portrait, landscape, and abstraction. Has the “progress” of painting come to a halt? I would argue that the linear notion of progress based on formal experimentation has been exhausted. Yet painting continues to expand in other directions: by emphasizing the trace of the hand and the presence of matter; by combining with other media, as in painting-installation; by responding to post-internet visual cultures; by probing personal identities; by addressing concrete political issues; and by reintroducing narrative. It is a mode of progress that suspends the forward thrust of linear time and unfolds horizontally.

The beauty of realistic painting still holds in relation to reality: realism is beautiful because it is truthful. Abstract painting is beautiful—not because of its image, but because of the aura of its material. Even a painting made from an insignificant photograph can be worth looking at. What matters is not the depicted object, but the act of painting itself. The reality of painting does not arise from a perfect resemblance to its object. It is generated as the painter fills the gap between what is seen and what is felt; that is the work of interpretation, and the way in which painting attains its own reality. And so I resolve to paint so that it becomes a painting.

Written by Dongwook Suh (Painter, Co-curator of Painting-like)